If Rob's and my trip had a theme or motif, I think it would have to be related to the climbing of mountains as a way of grappling with the unknowable.

Personally, I have always looked to the solitude of a walk in the mountains to mark the transitions of life. For me, this started in high school. It was opening day of a play I was in and I was nervous and finding a way to ground myself and focus. It was the last show I was going to be doing with my very best friends who were a year ahead of me and would soon be leaving for college. At that point in my life (and for long years after), experience had pretty much taught me that when people leave, they're gone, that transition meant a figurative death, that by moving into the next you lost all contact with the former, and that change was inevitable, came suddenly and cost you everything you had learned to love.

So, yes, I was a little low that day.

I went to high school in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and it was an easy, thirty minute drive from my front door to Skyline Drive. So that day, without much planning or forethought, I impulsively found myself up in the Allegheny mountains, looking out over the trees and foothills and farms, nursing a combination of sadness and exhilaration. I didn't have much time and I didn't need much time because it was one of those poetic moments that the teen-age me used to create self-consciously, praying for someone to notice. I always tended to craft those moments with an element of self-serving sabotage; alone on a mountain, it was unlikely that anyone would turn up to give me a hug.

When I got into my car to return home and get ready for the show, I flipped on the radio to see if I could get the good station from Charlottesville for a few moments before the mountain blocked the signal between my lame valley and the "cool" valley on the other side.

And what I heard was Supertramp's "Take The Long Way Home," specifically the section which went:

"And when you're up on the stage it's so unbelievable,

unforgettable how they adore you"

and I listened through the point in the song where they sang:

"Does it feel that your life's become a catastrophe?

Oh, It has to be for you to grow, boy . . . "

And I turned the radio off and my manufactured mountain moment was complete with a random dose of top-forty insight. And twenty plus years later, I may wish the music had been something other than Supertramp, but it was the early-eighties and that's what the universe was providing for a soundtrack. Besides, I loved Supertramp and sometimes you've got to wade through the shallow end to swim in the deep part.

Too many years later, when I was trying to figure out how to reclaim my life from poor choices and inertia, I returned to that mountain every year on my birthday, to walk a very small portion of the Appalachian Trail and think. And it became customary for me to seize the opportunities as they came along--with or without an actual mountain--to step off the path and process when I needed some time to think about the changes going on all around me.

So when Rob told me that it's a tradition in Japan to climb Mount Fuji in July and August, I didn't need to think too hard about it. And when he said that he wanted to do the two-mile climb at night, so that we'd be sitting there at the top when the sun came up, I hesitated for a moment and figured, if that's the mountain he wants to climb, then I'm going along.

But.

When we got there at five in the afternoon, tired, a little hung-over with too little cash in our pocket, we had to come to grips with a couple of basic truths. For one thing, we didn't have enough money for the expenses that the hike would accrue. You see, we'd have to pay for the taxi which would take us to the bus which would take us to the point where we could begin the hike. And, then we had to factor in the return trip which--although it covered the same distance, and traveled the same road as the trip there--was twenty dollars more expensive. Also, we needed to be able to stop and buy water at the various way-stations along the upward path. Also, it's a two-mile hike up a serious volcano in the dark and we would need flashlights and warm-clothing for an ascent into the thin air and cold weather of the summit. When we added it all up, we figured we could squeak by with our available cash, barring no disasters, and make it back to the hotel with about five dollars to spare and a bone-deep chill.

(As a side-note, I should point out that, yes, we asked, but the only ATMs in the area were located in the lobbies of the banks which were closed for the weekend. To be clear: Yes, there are Automated Teller Machines, but they are not available when the bank is closed. You may call this a fundamental misunderstanding of the benefits of ATMs or you can chalk it up to a country with serious control issues.)

Anyway.

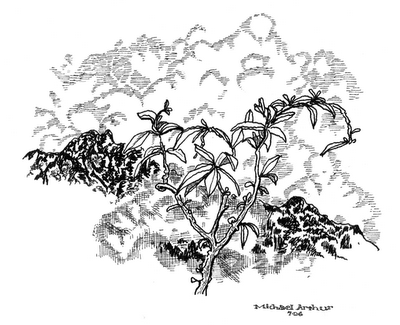

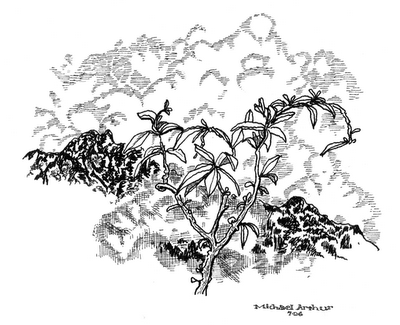

The final complicating factor was that, although we had arrived at the base of Mount Fuji, the actual mountain was nowhere to be seen. All around us was mist and clouds and the exquisite beauty of lakes and foothills.

"Maybe that's it," I would say to Rob, pointing to an obscuring cloud climbing over a patch of trees above. "I think it's there," Rob would say, pointing to another patch of mist. "I bet it's there," I would counter pointing across the lake and imagining the scene before me as rendered by Hokusai.

I dunno where it was, to be honest. And no one ever pointed it out and cleared the whole matter up. Like the fifteenth stone at Ryoanji, it just couldn't be seen, no matter where we stood.

And somehow, as we sat there together and gave up on the idea of climbing this mountain we couldn't see and sank into the satisfaction of the road which had brought us to this point, a sense of peaceful completion settled in.