My brother, Ben, and my sister-in-law, Heidi, have a “bear” theory of art. Well, maybe not a theory as much as a way to classify certain metaphors and recurring themes of an artist. They call these things “bears” because of John Irving and the way bears always turn up in his books.

Last week Ben had to drive about an hour out of town to pick up some tile for his new bathroom and I went with him, both to keep him company and because I am a bored man trying to fill the time when I am not working. And, right now, I am between assignments. Also, I like hanging out with Ben because we are both struggling artists trying to find meaning in life. Besides, he was going to Target and I needed cheap underwear and socks and that’s as close to meaning as I’m destined to get this week.

Anyway, we got to talking about our bears. You can get Ben’s album, Edible Darling (check it out at Amazon.com), and try to figure out his bears for yourself. Or you can wait until one of his novels or short stories gets published and then wait for the cliff notes version and figure it out from there. I’m here to tell you that his bears are fierce.

My bears tend to star-gaze and be startled by seismic changes in the known world; changes that are fundamental and sudden. These bears are wistful and sad. They like to see the best in things, and are always prepared for and surprised by the worst. My bears also tend to be missing paws and bellies and faces sometimes, but you can still see them if you look. If there’s one thing that theatre teaches you, it’s that the things that are left out can be the things that you see the best. Absent bears can growl louder than the ones in the room.

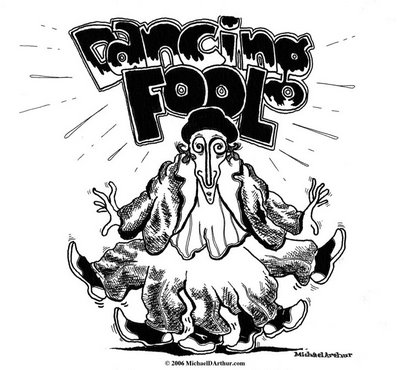

But I also have this dancing bear and I’ve had it a long time. As far back as I can remember, I’ve been drawing people dancing with abandon, feet in the air, fingers akimbo and musical notes floating all around.

I don’t know where the dancing bear comes from, because I don’t really dance and I was never all that interested in it. Back in college, when I was studying to be an actor I had to take a ballet class and a jazz class and a tap class and I was a clumsy, self-conscious three-left-footed bozo about it. When we took ballet, my room-mate and I used to say that the only step we could master was the Faux-pas.

Oh, how we laughed about that one. I still whip that joke out a couple of times a year; it’s got legs that one.

When I moved to New York and started drawing theatre rehearsals, I had no idea I would spend a good portion of the next six years of my life in ballet and modern-dance studios watching fancy dancers hone their craft. That one came from so deep in left field, you would think the guy selling hot-dogs threw it into play. In fact, when I first met the woman who invited me in to draw ballet, she asked me if I had ever heard of American Ballet Theatre and I was lying through my teeth when I said “oh, sure.” See, I knew ZIP about that world and I had never heard of ABT and I’m ashamed to admit it. But she saw my drawings and made a call and got me into the world that's been home ever since.

By the way, Blaine, if you’re reading this, I’m sorry I lied, but I will be in your debt forever for the way you changed a lying fool’s life with your kindness and generosity that day.

Anyway.

Three days after Blaine worked her magic, I found myself on stage at the Metropolitan Opera House watching the greatest dancers in the world getting ready to open Taming of the Shrew, and I was drawing to save my life, my dignity and cover my ass. At the time, I couldn’t even draw a full body, let alone a dancer. I just sort of drew hands and feet floating in the air. And suddenly I had the weight of being an artist worthy of being in the room with these people hanging on my shoulders and, for no reason I can think of, it felt like Responsibility. On the second day, I stopped in the gift-shop at The Met on my way backstage, just so I could look at some books and post-cards to sort of see what I should do. And I looked at Degas. And I looked at Edward Gorey’s ballet drawings and I thought, “Oh Jeez—there’s a history here. And I could be a part of it.”

I went to the stage door, filled with the (in retrospect, arrogant) idea that this art-form was mine now, and took the elevator down to the large studio in the basement and I drew a picture of Vladimir Malakhov turning multiple jetes in a striped body-suit and it didn’t look half bad, and I thought, “wow, I did it” and before I could finish patting myself on the back, this imperious ballet mistress said to me, “right, you’ll draw me next.” And it’s been like that ever since. Every time I do something I like, I realize it’s just a warm up for the next one. And I love that. I freaking love that.

I learned everything I know about dance and drawing the human figure from American Ballet Theatre, The Martha Graham Dance Company, David Parsons, Jacqulyn Buglisi, Donlin Foreman and Paul Taylor. And if you don’t know who they are, don’t feel bad, because neither did I until I was sitting in the room with them. But ABT is home to me. It's the place where I committed to this thing. It's the place where the dancing bear left the confines of my gazed-upon navel and stepped up onto a real stage. And it's the place where my drawing leaped forward because I was among like-minded people who worked every day to be better than they were.

Tonight I get to go to the season-opening, gala-performance of American Ballet Theatre at the Met. I’ll be a guest of Susan Jones, one of the ballet mistresses who became a close friend in the years I drew the company. I’ll be sitting there with all the society swells and hairdos that look like they were sculpted by abstract expressionists and I will feel as out of place as I always do at these things. And even though, Susan’s giving me only one ticket, I’m bringing the bear, because you gotta dance with the one what brung ya.